- Appearance: observe the appearance, including color and clarity.

Clarity: Most varieties of sake are clear. Except for nigorizake and so-called unfiltered sake, which are intended to have a cloudy appearance, any turbidity in bottled sake indicates that it has not been properly filtered. Although not to the same extent as wine, sediment may form in bottled sake that has been stored for a long time.

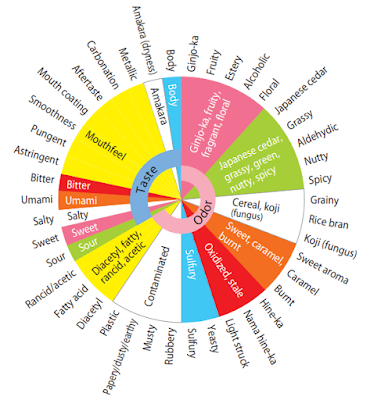

Color: Colorless, transparent sake is filtered using active charcoal to stabilize the quality. This treatment removes impurities and color. Sake that is not treated with active charcoal may retain a pale yellow color. The color of koshu, or sake that has been aged for a long time, ranges from gold to dark amber. This color results from the reaction of the sugars and amino acids in the sake. Sake also discolors if it is stored at high temperature or exposed to light for a long period. - uwadachika (orthonasal aroma): evaluate by bringing the vessel up to

the nose and smelling the aroma given off directly by the sake.

Fruit – apple, pear, banana, melon, lychee, strawberry, citrus: Ginjo-shu is rich in aromas suggestive of tree fruits, such as apple and pear, or tropical fruits like banana, melon and lychee. It is these aromas that are referred to as ginjo-ka. The element “ka” means aroma. The aroma comes from the esters produced by yeast in the fermentation process and is analogous to the secondary aroma in wine. To make sake with ginjo-ka, it is necessary to use highly polished rice and to employ painstaking care to create the right low-temperature conditions for fermentation. This brewing technique is known as ginjo-zukuri (Sec. 8.5).

Spice – clove, cinnamon, fenugreek: Some varieties of koshu, or long-aged sake, may have an aroma suggestive of clove, cinnamon or fenugreek.

Nuts: Another type of aroma found in some koshu varieties is reminiscent of almond or walnut, while some forms of namazake may have a hazelnut aroma.

Grass / green – cedar, green grass, rose: Taruzake, or sake that has been stored in cedar casks, has a wood aroma, called kiga, which derives from the cedar used in the cask. Some sake varieties have an aroma evocative of green grass or roses.

Cereal: Certain types of junmai-shu have a grainy aroma similar to that of the rice from which sake is made.

Fungi: Koji has an aroma similar to mushroom. This comes through in certain types of namazake and young sake varieties.

Caramel – honey, brown sugar, dry fruits, soy sauce: Because sake contains large amounts of amino acids and sugars, it acquires color and a sweet burned aroma due to the Maillard reaction during aging. This ranges from a honey-like aroma to one resembling soy sauce, brown sugar or dried fruit in the case of koshu varieties that are allowed to age for several years.

Acid – vinegar, yoghurt, butter, cheese: Depending on fermenting conditions, some varieties of sake have an aroma similar to butter or cheese, or a vinegar-like aroma - Taste and texture (mouthfeel): The first tastes noticed after taking sake into the mouth are sweetness and

sourness, followed a little later by bitterness and/or umami, which are most

readily sensed at the back of the tongue. Also experienced are the texture

attributes of astringency and smoothness. The finish (aftertaste) is experienced

after swallowing or expectorating the sake.

Amakara (amakuchi or karakuchi), sweetness or dryness: The balance of sugars and acids determines whether sake tastes sweet or dry. Increasing the acidity will reduce the sake’s sweet taste even if the amount of sugar remains the same.

Notan (nojun or tanrei), body: The sugar level and acidity also affect the sake’s body. Sake with a high sugar and acid content is regarded as rich or heavy. Amino acids and peptides also contribute and high levels of these result in full-bodied sake. A full-bodied variety may be referred to as having koku or goku(mi) .

Two Japanese terms used to denote the level of body are tanrei and nojun. Tanrei conveys the notion of “light” as well as “clean” and “sophisticated.” Nojun, on the other hand, conveys the meaning of “full (rich)” along with “complex” and “graceful.”

Umami: Umami refers to “savoriness” or “deliciousness.” A key amino acid associated with umami is glutamic acid. Sake is richer in amino acids than wine or beer, and contains a large amount of glutamic acid (Table 1.1). Adding glutamic acid to sake, however, does not boost the sensation of umami. This is probably because the umami of sake derives from a harmonious blend of numerous amino acids and peptides.

Nigami, bitterness: Bitterness is not a desirable trait in many varieties of sake, but it is one of the characteristics that give long-aged sake its complexity.

Kime, smoothness: An appropriate level of aging reduces any roughness or pungency to produce a smooth, mellow sake.

Kire, finish or aftertaste: In high-quality sake, regardless of whether it is sweet or dry, heavy or light, the taste is expected to vanish quickly after it leaves the mouth. This is referred to as kire. Unlike wine, a long finish is not regarded as a desirable characteristic of sake.

Taste and texture (mouthfeel): The first tastes noticed after taking sake into the mouth are sweetness and sourness, followed a little later by bitterness and/or umami, which are most - Faults

Zatsumi, unrefined or undesirable taste: Balance (or harmony) is a key requirement of the taste of sake. A disagreeable, unbalanced taste that cannot easily be identified as bitterness, astringency or umami is referred to as zatsumi. Sometimes zatsumi results from the use of inferior ingredients or poor brewing technique, but it may also be caused by poor control during distribution. If sake is exposed to light or high temperature during the distribution stage, the level of zatsumi will increase along with changes in color and aroma.

Lightstrike Light is the enemy of sake. The amino acids and vitamins that are plentiful in sake degrade when exposed to light, giving the sake an unpleasant musky smell.

Hine-ka, oxidized or stale odor: In addition to acquiring a caramel-like smell, sake that is stored under high temperature or conditions favoring oxidation develops an unpleasant smell like rotten cabbage or gas. This is caused by sulfur compounds in the sake. It is believed to be emitted by substances resulting from the metabolism of amino acids containing sulfur.

Musty (corky) smell: Sake bottles are not corked, but sake may on rare occasions acquire a corky smell.

Tasting notes for various sakés

Comments

Post a Comment